UNIT 1

From Evolution in Isolation to Globalization

Activities in this Unit:

- Introducing Invasives

- What’s in a Name?

- Timeline

- Where Do They Come From? Where Can They Invade?

- Invasive Species Jeopardy

UNIT 2

Summer Every Day and Winter Every Night

Cultural connections and ethnobotany. Watersheds and hydrology. Economics. Public heath and safety.

Activities in this Unit:

- “In Our Lifetime”: Kūpuna Stories

- Raindrops and Watersheds: Size Matters

- Frogs on Floor Four

- Plagues: Past and Present

UNIT 3

Biology and Ecology

Invasive Species Module, Unit 3: Biology and Ecology

Activities in this Unit:

What does the Invasive Species Zone Mean to You?

These reflections are offered by individuals involved in studying and protecting the native ecosystems of Haleakalā.

Invasive species are a nightmare.”

—Lloyd Loope

Some days it feels overwhelming – trying to stop the constant onslaught of new plants and animals coming to our shores. Maui Invasive Species Committee works on pests that run the gamut, from tiny ants to axis deer. We do it because if we don’t, we know what the consequences will be. We know that Hawaii and our keiki are too precious to stand by and do nothing.”

—Teya Penniman, Former Maui Invasive Species Committee manager

Ancient Hawaiians also reflected on blights on the land:

E ke akua … Pule ho’ola ‘aina

E ke akua:

He pule ia e holoi ana

i ka pō‘ino o ka ‘āina

a me ka pale a‘e i pau

ko ka ‘āina haumia

He pule ia e ho‘opau ana

i nā hewa o ka ‘āina a pau

I pau ke a‘e, me ka kawaū

I pau ke kulopia, a me ka pō luluka

I pau ka hulialana.

A laila, nihopeku, hō‘emu,

huikala, malapakai

Kāmauli hou i ke akua, e!

E ke akua…

Prayer to heal the land

O akua:

This is a prayer to cause cleansing

of the misfortunes of the land

and to ward off all

of the land’s desecration

This is a prayer to cause ending

of all wrongs of the land

that the blight ends, and moistness returns

that the decay ends, and the peace returns

that the bitterness ends.

And therefore, buds-shooting, weeding,

complete cleansing,

Renew offerings thanking the akua!

NOTE: This pule can be found in Malo (p 199). No particular akua is specified in this prayer to remove blights and other problems from the land. It is presented here as an example of the kind of prayer that might be used to ward off diseases and other crop problems as part of the cycle of agriculture in Hawai‘i. It is interesting to note that disease and other misfortune is linked to desecration (haumia) and requires spiritual cleansing (huikala) in order to right the wrongs and bring healing and renewed growth

Where on Haleakalā?

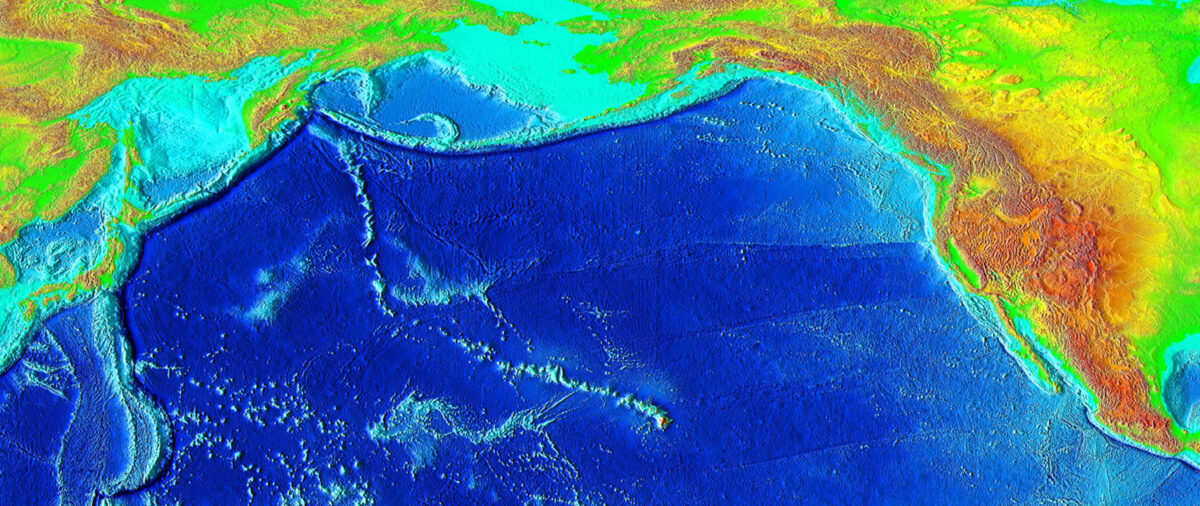

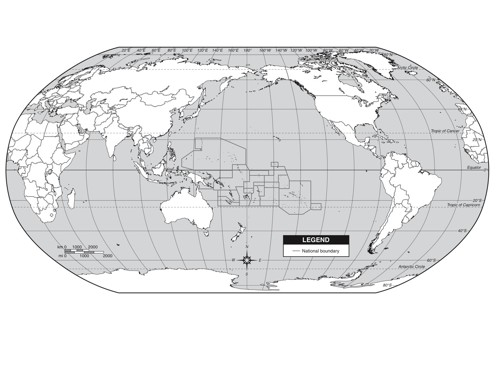

Invasive species affect every ecosystem in the Hawaiian Islands, from the regions deep underwater to the summit of the tallest mountains.

Basic Characteristics

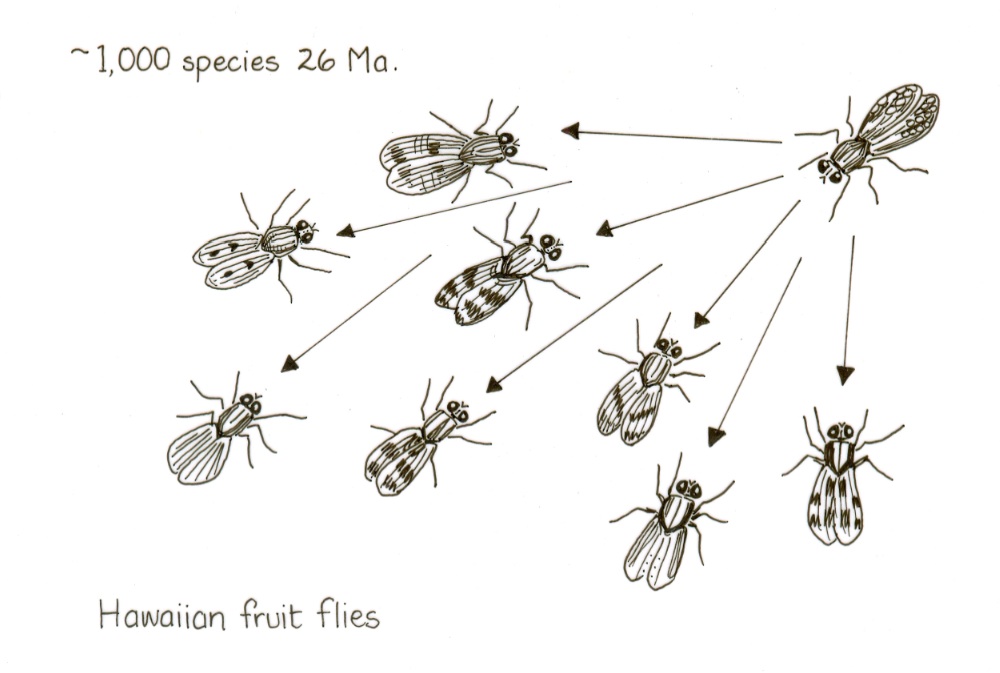

Invasive species are nonnative species whose introduction causes or is likely to cause harm to the economy, environment, or human health. They directly prey upon or outcompete native species for resources.

Invasive species can be plants, animals, insects, or microorganisms, such as bacteria, fungi, and diseases.

Did You Know?

The first invasive species to reach the Hawaiian Islands was likely the Polynesian rat, which hitched a ride aboard the Polynesian voyaging canoes.

Status and Threats

Biologists consider invasive species the number one threat to native Hawaiian ecosystems–though global warming may soon override invasives. Currently, invasive species in Hawai’i are managed by a number of state, federal, and private agencies. Organizations such as the National Park Service, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Hawai’i Department of Land and Natural Resources, The Nature Conservancy, and the invasive species committees and watershed partnerships on each island make it their mission to prevent harmful alien species from spreading throughout the Islands.

Traditional Hawaiian Significance

Native Hawaiian cultural practices depend on healthy ecosystems, which are endangered by invasive species.

Before contact with Western explorers, Hawaiians made everything they needed out of what they found in the natural environment. Plants provided the raw material for houses, canoes, clothing, food, fires, lamps, tools, surfboards, musical instruments, medicines, and much more.

Early Hawaiians chose sturdy ‘ōhi‘a (Metrosideros polymorpha) branches for their house posts and thatched their roofs with lauhala (Pandanus odoratissimus) and loulu (Pritchardia spp). They made clothing out of wauke (paper mulberry) dyed with ‘olena (Curcuma domestica), lit up the dark with kukui (Aleurites moluccana) nut oil lamps, and rode waves on surfboards carved from the wiliwili (Erythrina sandwichensis) tree.

Invasive pests and diseases such as ‘ōhi‘a rust (Puccinia psidii) or the wiliwili gall wasp (Quadrastichus erythrinae) have the potential to wipe out the native Hawaiian species they prey on within a single season.

Hawaiians had an intimate bond with their natural environment–and many still do. They believe that certain native plants and animals are kinolau, physical manifestations of gods, or ‘aumakua, physical ancestral spirits. They treat these species accordingly, with respect and reverence. They even view weather patterns—certain types of rain, wind, or rainbows—as kinolau and ‘aumakua. When aggressive, introduced pests erode the integrity of native ecosystems, crucial pieces of the Hawaiian way of life are lost.

Journal Ideas

Use some or all of the following topics for student journal entries:

- Listen to the chant as it is read in Hawaiian. How would you describe the feeling of the chant? What did it make you think about?

- Listen to the English translation of the chant. Do you have different thoughts and feelings now that you know what this chant means in English?

- Have you ever been on the road to Hāna? What are your impressions of this area? Most of the vegetation you see along the highway is non-native and some, such as the large patches of strawberry guava and bamboo, are invasive. Does knowing this change how you feel about it?

To Get a Feel for the Invasive Species Zone

Examples of forests dominated by invasive species can be seen along the Hāna Highway. Notice the huge patches of bamboo, the thick strawberry guava stands, and the bright orange flowers of the African tulip tree reaching far up the mountain. These species have replaced the native plants and trees that once flourished here.

Here is a perspective on invasive species written in April 1986 by Sam ‘Ohu Gon III, senior scientist / cultural advisor to The Nature Conservancy:

A World of Weeds

When we go hiking, we are some times lucky enough to see a portion of trail that has almost no weeds on it: almost purely native plants, a canopy of ‘ōhi‘a in red bloom above. At our feet the roots meander across the trail, packed with wet mosses and small ferns, dozens of different kinds of them in a small space between two trees. An ‘ōlapa trembles in the wind, flashing sunlight off of glossy, oscillating leaves, and a tall hāpu‘u, with purple-red bristles, sends large fronds above our heads, dappling the sunlight below, where orange-berried makole sends its offshoots among the liverworts. The cool smell of growing plants and spongy leaf litter combines and moves on a ko‘olau breeze…

Most of all, we get a feeling of balance. What a diversity of living things, and not too much of any one of them. Sometimes I envision just a couple of square meters of it, that’s all, not too much to ask…placed in a small corner of the yard, there to be the model for any gardener, and almost impossible to duplicate or maintain because of the narrow requirements of temperature and moisture. And because of weeds. In a month, even if all of the mosses could persist, the dandelions, Spanish needles, three-leafed clovers, and beggar’s ticks would be in there. Weeds.

But what’s a weed? Something that’s growing where it is not wanted. The rarest prairie wildflower, introduced to the native subalpine grasslands of Haleakalā, might be a weed there. We can all appreciate what trouble weeds can be. Maybe we are already aware of banana poka, a passion-fruit relative, climbing like a blight over the tops of koa-‘ōhi‘a forests on Hawai‘i Island. It hogs the light, so that under its green net are sun-starved native plants, skeletons of trees, open soil. Or perhaps we have walked through an unexpected blackberry patch on Ka‘ala, or in Kōke‘e, and recalled adjectives and dark thoughts while nursing thorn-shredded arms and legs. Or we’ve seen the sad spread of Clidemia on O‘ahu, Moloka‘i, Maui, and Hawai‘i: gulches full of nothing but purple berries and crinkled leaves, where we once breathed in the scent of native mints in full bloom. Aloha ‘ino!

Why is it that weeds always grow so fast? Taste so bad? Prickle and poke? It is their strategy. They are colonizers, adapted to establish a foothold and hold it in a disturbed situation: a landslide scar, or scoured flood plain. And we are great disturbers, too, aren’t we? Road builders, sub-dividers, and yes, trail builders too. Is it any accident that Clidemia followed O‘ahu hikers and hunters on their trips to Wailau and Waimanu?

We are the keepers of the land. We need to make a choice. For me, I have made a judgment that a native plant, no matter how plain-flowered, how small, how unremarkable, is inherently more valuable than any ornamental. Oh, there are beautiful introductions to be sure! But so many of them are splashes of color, spectacular to experience, and striving to out-do. But there is much to say about subtle beauty too. A concert of diversity in a native forest is a hum of quiet harmony and delicate shades.

Well, we can make a choice. I can envision a horrid world, where the only things that have been able to survive with humans are those things that we couldn’t weed out: the thorniest things, the most poisonous, the things that crowd other things out, the cockroaches and flies, the things that thrive under our streets and on our waste. It is a world that comes if we don’t care. Because when we don’t watch the garden, the weeds come in.

Or, there is a world in which we value and care for native diversity because it makes us richer. We can listen to clear waters drip from mosses into a cold mountain pool, watch ‘ōpae sweep the rocks for algae, see a kanawao with tiny white flowers at its roots pollinated by diminutive beetles that work the soil. We can all stand to learn what is really valuable in our islands: a diversity of things found nowhere else in our wide world, and a beauty that is the antithesis of neon-emblazoned ideas of what is visually appealing.

And the best thing is that these riches are not gotten via corporate maneuvering, labor unions, or business degrees. We can all enjoy these riches without kicking someone else off a ladder. Mai e loa‘a i ka waiwai o ka ‘āina – Come partake of the riches of the land.

Search Curriculum by Activity

Use our grid below to search for a specific activity by unit, type, or topic.